2.II.2. Invent the influence on regulation

This is part of the book “Stéphane Foucart et les néonicotinoïdes. The World and disinformation 1“ where I show the journalist misinforms (= false or misleading statements) the reader. One of the myths he develops is that the regulatory response against NNIs has been delayed by industry influence. All quotes are translated (by me), except the ones marked between [ ] in the french version (french quotes are to numerous to be marked in this one).

The recognition of this (invented) consensus would have been delayed by the influence of the industry on the setting of health standards and on scientific reports. To defend this thesis, S. Foucart invents an influence and gives it credibility with his manipulation procedures. This influence would be betrayed by conflicts of interest.

To make his conception of the conflict of interest credible, the journalist presents environmental groups and industry and health agencies as fundamentally different sets. This mechanism essentially has two branches:

- An asymmetry in the credibility of scientific studies (he presents in the most negative light the studies that contradict him and highlights those that suit him; presents scientists with the slightest connection to industry as lobbyists)

- An asymmetry in the presentation of the “pressures” exerted. We have already seen it above: any “pressure” from industry is presented as terrible lobbying and any “pressure” from environmental groups is presented as a legitimate popular demand. Let us recall this short quote, which demonstrates it perfectly:

“The vote took place in a context of great tension, between intense lobbying by agrochemical companies and strong mobilization of the beekeeping sector.” (8)

However, first of all, let’s explore one of the foundations of this disinformation: a distorted view of the agrochemical industry.

a. A caricatured presentation of the sector

The journalist’s entire argument is based on a caricatured vision of the industry, which is said to develop increasingly toxic pesticides. We have already seen in part “I.3.An agrochemical industry pushing toxicity? Of this chapter that it did not hold. The author also presents a caricatured image of regulatory tests:

“A regulatory consensus is based on the opinions of expert agencies which judge the compliance of a product with the regulations in force. These are often anonymous opinions, not subject to peer review, based on data generally confidential and inaccessible to criticism, produced and interpreted by the manufacturers themselves.” (50)

However, it is not the manufacturers themselves who perform these tests, but laboratories which have specific accreditation (Good Laboratory Practices, GLP) and are audited.

“- Suddenly, if a laboratory tried to please manufacturers to bring in more contracts, would it be penalized?

– I think these are risks that no lab would take. Because it is her accreditation that is at stake.” (Eugenia Pommaret, interview)

b. Good and bad scientists

As we saw in the second chapter, S. Foucart presents as having no scientific value any work produced by a person with even a distant link with industry.

“During its last conference, at the end of 2011 in Wageningen (The Netherlands), seven new working groups were formed on the issue of the effects of pesticides on bees, all of which are dominated by researchers in conflict of interest situations. The participation of experts employed by agrochemical firms or private laboratories under contract with them varies between 50% and 75%.” (2)

At no time does it justify the relevance of this posture. Why would scientists employed by an industrialist suddenly lose all freedom of expression and all scientific integrity? It is even more incomprehensible to the employees of private laboratories: why would they flatter the firms? Why would they agree to compromise themselves? For what concrete advantages?

It is as if he absolutely denies any form of integrity among researchers who choose to work in or with industry! Any vague potential interest would justify them putting it aside altogether and bending over backwards to meet the expectations of the pesticide producer. It turns absurd when he talks about researchers employed by laboratories with contracts with firms. There is no longer even a direct interest!

To compare, imagine: you work at Mac Donald, are you systematically going to push your friends to eat there? Even as soon as you get the chance? Likewise, imagine a janitor who works for Monsanto: does that make him someone who will defend the firm through thick and thin? What is the difference with a scientist?

Public researchers are also subject to the same issues:

- They must be attractive to public authorities in order to be able to mobilize subsidies.

- They can be encouraged to appeal to a specific audience to gain notoriety, credibility and sell various services (the most obvious being the book).

I have already mentioned in Le Cancer Militant (Baumann 2021) the many rewards, social, psychological or material, that activism can generate (on this topic, I invite you to read Daniel Gaxie). Note that we have seen this mechanism at work precisely on the subject of the NNI: Vincent Bretagnolle, researcher at the CNRS militant against the NNI, has converted into political capital, the notoriety he has gained through his publications and his takes of position. He was in fact on the EELV list “Our terroirs, our future, ecology now” for the regional elections of Nouvelle-Aquitaine in 2021. In short, if S. Foucart applied sincerely his conception of the conflict of interest, he would no longer quote anyone…

c. Industry’s direct pressures

The author presents as terrible the pressures from industry to describe, in fact, trivial acts. Here for example:

“This time, European expertise came under intense pressure. Several letters sent by Syngenta to the EFSA general management, made public by the non-governmental organization Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), show that the Swiss agrochemist has demanded, in vain, amendments to EFSA’s position , going so far as to threaten some of its prosecutors: “We ask you to formally confirm that you will rectify the press release by 11 am, write Syngenta executives to an EFSA official on January 15. Otherwise , you will understand that we are considering legal options.”” (8)

Letters, realize! Legal remedies! It is easy to imagine the fear felt by the officials who received these letters… You get it, it is ridiculous: these organizations have dedicated legal services and are used to this kind of challenge. Dealing with appeals from organizations unhappy with your regulations is part of the daily life of any regulatory body. S. Foucart, however, presents this as “intense pressure”.

d. Accusations that “flop”

The precariousness of S. Foucart’s accusations is perfectly clear when he came forward to criticize IPBES and IUCN. He attacked them before they released their report and ultimately found nothing to say. In neither case did he come to a conclusion: it is as if he had never been wrong.

IPBES

The author strongly questions the credibility of IPBES in several articles, noting that two employees of agrochemical companies are responsible for chapters of the report on pollinator decline. (19) (24)

The report in question having in the end produced a report in line with his expectations, he repeats it in an article and qualifies the institution as “IPCC of biodiversity” (as it stood). He nevertheless maintains his suspicions, affirming in the same article that “This paragraph [on the role of pesticides] will be scrutinized” (25). In the end, he had nothing to say…

This did not prevent him when, when asked about it in the context of the promotion of his book, to state in substance that the presence of employees from the industry had nevertheless had an influence:

“It is impossible to determine the impact that this person’s participation in the work of IPBES had in the end, but the history of science work carried out on the tobacco industry’s influence strategies – in particular those of the American historian of science Robert Proctor (Stanford University) – shows that the participation, in expert work, of researchers in conflict of interest has the effect of biasing its conclusions.” (57)

Heads up, he wins; stack, you lose.

L’UICN

The journalist extensively questions the integrity of IUCN in his article of May 5, 2014 (17), as we have seen above. Yet he cites this organization as a reference in the article on IPBES, just a few months later (19):

“The International Union for the Protection of Nature (IUCN) estimates that 16.5% of vertebrate pollinator species (birds, bats, etc.) are threatened with extinction, and up to 30% for species islanders. “

Once again, no questioning a posteriori. His complaints came to nothing: neither confirmation nor mea culpa.

L’AFSSA

What S. Foucart writes about AFSSA (former name of french health agency) is quite terrible:

“But it is true that certain ‘expertises’ have maintained political power in a ‘socially constructed’ ignorance on the subject. The history of science will probably judge with severity the various reports – such as the one made in 2008 by the defunct French Food Safety Agency (Afssa) – taking up, sometimes in questionable conditions of integrity, the vulgate of agrochemists: since bee disorders are “multifactorial”, new phytosanitary products do not play a decisive role. ” (9)

It provides absolutely no evidence to support any industry influence on these estimates. These allegations are all the more defamatory since, as we have seen, the multifactorial nature of the collapse of the hives was (and still is) simply the state of research, which can be found in both public and public researchers. at health agencies.

La FERA

The journalist refers to a report by FERA (the British health agency) and heavily suggests that he was influenced by Syngenta. (21) (24) What factual elements does it provide?

- A researcher very involved in the denunciation of NNI, Dave Goulson, finds by analyzing the raw data of the report, conclusions contrary to those of the latter.

- “Asked by the Guardian, a spokesperson for FERA more or less ate his own hat.” (21)

- Helen Thompson is believed to be the lead author of the study and, shortly after reporting her findings, joined Syngenta.

Regarding the first point, one can immediately underline that this is only the opinion of a researcher. Is this criticism founded or not? We do not know. The author writes, “This reanalysis has not been contested.” Should we believe it? Does that mean it’s fair or that no one bothered to answer it? Either way, even admitting that the criticism is correct, that would prove nothing: there would just be a bias that was not taken into account. What could be more ordinary? Moreover, by reading the article in question (Goulson 2015), we see that the demonstration seems a little surprising. For example:

“Residues of chemicals were often below the limit of detection (LOD), and simulated values between zero and the LOD were assigned randomly assuming a uniform distribution.”

So he invented data in a totally arbitrary way (why choose “a uniform distribution”? We don’t know.) Without going into it, we can clearly see that he is making some rather strange and complex calculations. We are really in the register of scientific discussion, not of denouncing an obvious sham (for an example of this register, I refer you to what we said about the study by Hallman et al. 2017).

Regarding the second point, it is difficult to see what S. Foucart is talking about: it is doubtful that the headgear of the spokesperson in question is edible. This is probably an allegory that he admitted the report was biased and wrong. However, it is unclear and finding the article in question would have been much easier if he actually cited it… I found a Guardian article on the subject containing a reaction from a spokesperson for FERA. This is what he says:

“Dr Thompson’s move is a reflection of her expertise and international reputation within the scientific community. There is no conflict of interest. There are very specific rules for civil servants governing the acceptance of appointments outside the civil service.”

Another post, after Goulson’s study, is more promising, a spokesperson for FERA saying:

“In the executive summary of our 2013 report we clearly stated that our experiment lacked the power to reach any firm conclusions about the impact of seed coated neonicotinoid on bumblebee health. Whilst there was an absence of evidence to support the hypothesis that neonicotinoids harm bees, this does not lead to the conclusion that they are benign”.

In short, the study would not have been conclusive. So where does he “eat his hat”? I do not see. Note that what he says has nothing to do with David Goulson’s claim that the study is “the first study to describe [their] substantial negative impacts” in real life.” (21)

Regarding the third point, we find the extreme vision of S. Foucart of conflicts of interest. Concretely, how would the researcher have done? Would she have skewed her report first without her colleagues noticing, then went to Syngenta and said, “Look, I helped you even though you didn’t ask me, now hire me and give me a great deal!“? Or would Syngenta have dispatched a secret agent to offer her the exchange of good deeds, at the risk of being exposed and prosecuted for corruption? You see that as soon as you dig, the journalist’s story is full of loopholes. If you want a “story” that is plausible, you can tie those elements together very differently: Faced with pressure from environmentalists, Thompson saw his career (and life, because seeing his credibility constantly questioned isn’t pleasant) to FERA to close and chose to join the private sector. Not only does S. Foucart prove nothing, but in addition hypotheses that are totally contrary to his storytelling are more credible than the absurdities he puts forward.

The design of industrial standards: the general insinuation

The author defends the idea according to which manufacturers would have had a significant influence on the creation of the tests to be carried out to approve pesticides and that this would explain in particular the flaws highlighted in these procedures by the EFSA report of 2012. (2) (39)

However, it allegedly “shows” that industry-related scientists were involved in their development processes:

- “The participation of experts employed by agrochemical firms or private laboratories under contract with them varies between 50% and 75%. The other members are experts from national health security agencies or, more rarely, scientists from public research. Pesticide manufacturers therefore play a key role in the design of tests that will be used to assess the risks of their own products on bees and pollinators.” (2)

- “Manufacturers have therefore, in a way, created the very scientific framework in which the evaluation of their products is carried out”. (39)

” How is it possible ? It’s not very complicated: these protocols were designed by groups of experts infiltrated by the agrochemical industry. In a report released this week, Pesticide Action Network (PAN) and Future Generations suggest that this example is not isolated. On the contrary, it falls within a standard. The two NGOs reviewed twelve standard methods or practices used by public expert agencies to assess the health or environmental risks of “phytos”. Result: in 92% of the cases examined, the techniques in question were co-developed by the manufacturers concerned, directly or indirectly.” (39)

We find his absurd conception of the conflict of interest: any presence of a person with a vague connection to the industry would be a kind of indelible stain. It rarely specifies how (beyond generalities) this conflict of interest would be implemented in practice.

He did venture there once, however. This is what we are going to see now.

The design of industrial standards: the EPPO

In the article (2), “The bankruptcy of the evaluation of pesticides on bees”, the journalist claimed to explain the flaws in the evaluation procedures highlighted by a 2012 EFSA report (Boesten et al., 2012) by the influence that had manufacturers on the enactment of said procedures.

We will extensively presented the (many) manipulation methods of this article in the fourth chapter. This time, let’s just study the facts he raises that can support his thesis:

- The “guidelines for these tests were notably issued by the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization [EPPO]”. The others would be decreed by the OECD.

So we have some guidelines issued by this EPPO.

- This organization allegedly delegate to the “International Commission on Plant-Bee Relationships (ICPBR) – the task of developing the basic elements of these famous standardized tests. “

The author suggests that this commission would be entirely responsible for this development, in particular noting that the EPPO would have “no in-house expertise”. This does not really make sense given that it is made up of GOVERNMENTS and that after this commission has issued its report, the latter mobilize experts to assess it and are ultimately the sole decision-makers.

But back to the ICPBR.

- The fact that the final recommendations of the group are based on a “consensus approach” would “de facto place the recommendations from the organization in the hands of the industry. Because the ICPBR is open to any participation and agrochemical companies are well represented. In 2008, of the nine members of the bee protection group, three were employed in the agrochemical industry, one was a former employee of BASF and another future employee of Dow Agrosciences. “

First of all, he insinuates that being a future or former employee of a company qualifies as its “representative”. Does he believe that there is some kind of eternal blood pact when you go into this kind of business?9 Did the future employee already know the future? It is not even made clear whether or not the employees represented their employer. Even being an employee does not mean that your words are dictated by your employer (unless you may be there to represent them). So the fact that the “firms” dominate the group is debatable and it would still only be a working group, which should present its work to the whole, which should present it to the Member States …

Second, how would this consensus approach put the process “in the hands” of the industry? I don’t even see what to discuss: not only does S. Foucart not justify his allegation in any way, but I don’t even see what it could possibly be. Above all, it seems absurd: it totally contradicts what the journalist said, suggesting that a group could, thanks to the numbers, dominate the whole …

But it is not all!

- “In 2009, a few months after the Bucharest conference, the final recommendations of the ICPBR were submitted to the EPPO. But before being adopted as official standards, they are subject to review by experts mandated by each EPPO member state. “

After being reviewed in plenary session, the recommendations are therefore submitted to the dozens of EPPO governments for consideration, as follows:

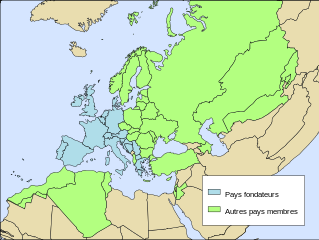

We note the presence of all the former Soviet bloc, Turkey, Jordan… It is difficult to see how these countries would have agreed to seek to support Syngenta (Switzerland), Bayer-Monsanto (Germany), Dow- Agroscience (US), BASF (Germany), etc. This is all the more ridiculous since the USSR itself joined the EPPO in 1957…

- Summary

Thus, to summarize, we would have three employees of the “agrochemical industry”11 and two former or future employees who would have decisively determined the conclusions of a group of 9 people (knowing that they should have convinced them all), then presented their work to other groups and would have convinced them collectively, unanimously, of its relevance. Then, it would have been necessary that NONE of the 52 Member States and their experts saw a problem, whereas there would be a “scientific consensus” on the matter (cf the preceding part)… And, all at the risk for the 3 scientists employed in agrochemicals to be identified as lacking scientific integrity by their peers. A hell of a story, don’t you think?

We have a procedure completely dominated by governmental institutions (which is logical, given that it is the principle of the organization…), which the journalist tries with a toolbox of rhetorical mechanisms (see chapter 3) to pass off as a system in which the influence of industry could play to the full. You see, even if we limit ourselves to what the author presents, we see that the main thesis (“manufacturers set the rules that govern them”) absolutely does not stick. It is the governments and their regulatory agencies that hold the power. This, by not even commenting on the veracity of what he is saying (which would be difficult, since he does not source…).

I do not go back to another claim from his article:

“During its last conference, at the end of 2011 in Wageningen (The Netherlands), seven new working groups were formed on the issue of the effects of pesticides on bees, all of which are dominated by researchers in conflict of interest situations. The participation of experts employed by agrochemical firms or private laboratories under contract with them varies between 50% and 75%. The other members are experts from national health security agencies or, more rarely, scientists from public research. ” (2)

Indeed: we have indeed already seen that this conception of the conflict of interest was delusional; he does not source his allegation; what we have just presented further invalidates his vision, it would still be necessary to convince all the other scientists, which is absurd and even logically incompatible with the idea according to which there would have already been a consensus on the dangerousness of NNI at this time.

Thus, S. Foucart invents an influence that the agro-industry would have on the establishment of regulatory standards.

Page bibliography

- Boesten, J., Bolognesi, C., Brock, T., Capri, E., Hardy, A., Hart, A., Hirschernst, K., Bennekou, S., Luttik, R., Klein, M., Machera, K., Ossendorp, B., Annette, Petersen, Pico, Y., Schaeffer, A., Sousa, J.P., Steurbaut, W., Stromberg, A., Vleminckx, C., 2012. EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues, scientific opinScientific Opinion on the science behind the development of a risk assessment of Plant Protection Products on bees, EFSA Journal. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2668

- Goulson, Dave. “Neonicotinoids Impact Bumblebee Colony Fitness in the Field; a Reanalysis of the UK’s Food & Environment Research Agency 2012 Experiment.” PeerJ 3 (March 24, 2015): e854. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.854.